This is the first in a series of three articles detailing the difficulties inner-city programs in Texas face in pursuit of on-field success.

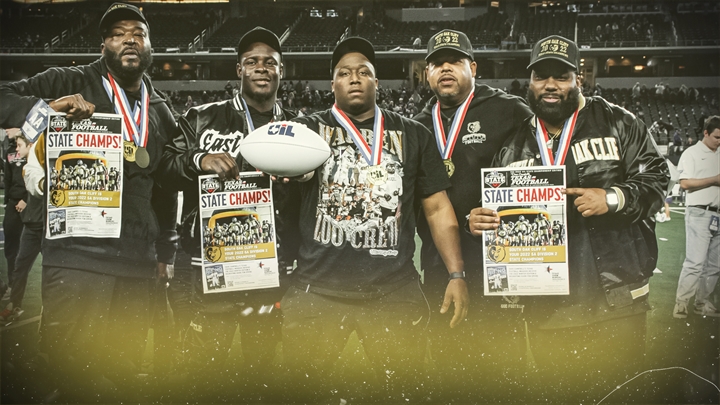

The gold chains around Jason Todd’s neck shimmered in the December sun as he raised the state championship trophy above his head to raucous applause.

Thousands of Dallas community members sprawled across South Oak Cliff’s state-of-the-art turf practice field. They’d followed the victory parade a mile down South Marsalis Avenue to the high school, a sea of black and gold celebrating the Golden Bears’ 23-14 win over Liberty Hill in the 2021 Class 5A Division II State Championship. The SOC faithful clamored before the stage to witness Dallas ISD’s first trophy since 1958.

South Oak Cliff’s 15–1 season had energized a community that could’ve lost hope of reaching this mountaintop long ago. Now, they hung on every word the head coach who’d brought a football title to the inner city had to say.

“I’m going to speak my truth today,” Todd said. “A lot of people start coming on with the belief, and that belief starts spreading and filtering. But this dream started a long time ago.”

The switch flips. The swagger in Todd’s voice increased with each sentence. His entire football team surrounded him at the podium draped in gold medals, and they nodded their heads as the memories flooded back to them of all they had to endure before they could stand exalted.

“They’ve been up here working out when we didn’t have a school,” Todd said. “When we didn’t have a football field. When we rode the bus to practice, and they got home at 10 p.m. every night.”

The trophy, the medals and the parade honored a storybook season that had validated Dallas ISD.

But the dream started when Jason Todd was promoted from defensive coordinator in 2014 at a school where winning a state championship was impossible. South Oak Cliff’s campus at that time prevented it.

The turf field where the community now gathered to celebrate didn’t exist then, and neither did the weight room with a wall-length mirror and dumbbells. Some coaches must manufacture an underdog narrative to make their team believe no one thinks they can win. At South Oak Cliff, where football players went to school in a building without a roof and practiced on concrete when their field flooded at the first hint of rain, Todd’s players had all the needed evidence.

So, Todd spoke for all those men that had laid the foundation for what the state championship team earned. Beside him were the players who’d started their South Oak Cliff careers busing around the city because they had no weight room or field and finished it as the example of what an inner-city football team could accomplish when given the right resources.

Todd is much more subdued this morning, now 15 months removed from the emotions of that historic celebration. Of course, there’s no crowd to hype him up as he gets situated for a typical March day of off-season work. But the shock of winning a championship in the inner-city has long since worn off. In its place is an expectation to compete for them every year. He’s no longer the head coach of an underdog, but rather a machine that’s the first Dallas ISD program ever to win back-to-back state championships, outscored its district opponents 752-41 over two seasons and sent 12 members from the Class of 2023 to play Division I football.

And at a point in his coaching career where his resume could land him a higher-paying college job, Todd instead chooses to chase more championships at a school where the unprecedented is the new reality.

“I’m trying to ride this wave because, in the inner city, this really hasn’t been done,” Todd says. “Every day, we’re writing history here. I just want to keep on etching our place in history.”

Since 2010, 52 Texas high school football teams have won a state championship in one of the top four classifications. Six schools won 46 percent of them.

Austin Westlake, Austin Lake Travis, Highland Park, Aledo, Katy and Allen serve as the model for what every high school coach hopes to build: a program where the playoffs are a foregone conclusion, and the season is a disappointment if it doesn’t end with a trip to state.

But these schools have a few defining characteristics that can’t be replicated everywhere.

All except Highland Park, which exists on an island within Dallas ISD as its own school district, are in the suburbs of a greater metropolitan area. The average of all their student populations considered economically disadvantaged is 12 percent. And because the community is wealthy, these teams have well-resourced booster clubs that fund new equipment, catering and travel on game days, which lets the coaches focus on coaching.

Their dominance is a relatively recent phenomenon. Before the turn of the 21st century, these schools combined to win merely six state championships.

Houston and Dallas, the two largest school districts in Texas with 37 high schools each, are chock-full of teams with rich histories tracing back to the Prairie View Interscholastic League, where African American Texas high schools competed in sports during segregation from 1920-1967.

But as the suburban schools established dynasties, most Houston and Dallas ISD teams fell behind on the gridiron. Before South Oak Cliff’s back-to-back run, the last Dallas ISD team to officially win a championship was Dallas Washington’s 1958 title team in the PVIL. Dallas Carter’s 1988 state title was formally stripped by the UIL. Houston ISD’s last State title was Houston Yates’s 16–0 season in 1985, to some considered the greatest team ever assembled.

The former PVIL teams are a relic of the past, and in their place is an acceptance that the inner city doesn’t have the resources to compete with the suburbs.

Both districts consist of a 90 percent minority population. Houston counts 85 percent of their students as economically disadvantaged, while Dallas counts 78 percent. Both are well above the State’s average in chronic absenteeism and dropout rates.

Yet South Oak Cliff, which has a 99.2 percent minority enrollment and considers 94 percent of its students economically disadvantaged, enters the 2023 season in search of a third-consecutive championship. They chase landmarks that suburban dynasties were thought to have a monopoly on and throttle teams in their district with the same demographics and socioeconomic standing.

Their dominance didn’t come by accident or a stroke of good luck. It was fought for.

…

The Legacy Hall is the newest hallway in South Oak Cliff High School, added to the back of an entirely renovated building that opened its doors in January 2020. But it serves as a constant reminder of the school's storied past.

Students today file to their classes beneath the Walk of Fame, murals hanging from the ceiling depicting every principal that’s served the school. Alongside them is every alumnus inducted into the Dallas Independent School District Athletic Hall of Fame, Olympic Gold medalists like Chryste Gaines, and Super Bowl MVPs like Harvey Martin. With each step, there’s another example of a legend from this school, frozen in time as a pioneer who built South Oak Cliff’s legacy that the kids today are tasked with furthering.

Jason Todd’s grandfather, Dr. Frederick Todd Sr., is immortalized here, too, as the longest-tenured principal in the school’s history. Todd’s family lineage is entwined with Dallas ISD, so he’s never left. He played his high school ball at nearby Dallas Lincoln and coached there before South Oak Cliff under Reginald Samples, considered the godfather of Dallas football, at Dallas Skyline.

In addition to his duties as head coach, Todd describes himself as a Dallas ISD historian. So, amid unprecedented accomplishments as an inner-city football program, Todd speaks of South Oak Cliff teams’ successful seasons in the past.

The current program stands on the shoulders of those who came before them, those on the Walk of Fame who didn’t have the opportunity to attend this beautiful, renovated school they’re now honored in. Instead, they lifted weights in a hollowed-out room tucked beneath the school building, flipping flywheels over because they couldn’t afford dumbbells.

They also didn’t have the coaching staff that Todd assembled and has managed to maintain as other programs tried to pluck staff to get a piece of South Oak Cliff’s magic. Defensive coordinator Kyle Ward coached at Texas A&M and Boise State. Linebackers coach Domenic Spencer played under Todd at Skyline and went on to a four-year career at the University of Central Florida. Clarence Jones played at New Mexico and is now the defensive backs coach.

“When you compare SOC’s staff from that time,” Ward said. “I think we’ve got 18-20 coaches, and I might not be able to name a coach that didn’t play in college at his position.”

Ward oversaw a defensive backfield consisting of six Division I signees this past season, including All-District cornerback Jamarion Clark. Clark, an early enrollee at Rice who just wrapped up spring football, credits the coaching staff for honing his football intelligence. After countless hours in the film room by his senior season, Clark knew the opposing quarterback’s favorite route on any given down and distance and what coverage technique to employ before the ball was snapped.

“When inner city schools or Black teams win, the first line is, ‘Oh, it’s the athletes. They just have some superstar athletes,’” Clark said. “No, that’s not true. At SOC, coaching plays a very big role in our success.”

But the college-level weight room and access to information came after tremendous accomplishments from decades of athletes who competed without them, which is why Todd reminds his players constantly of the past. It’s why they built a Legacy Hall.

“It’s about understanding that you’re not the first to do something great,” Todd said. “We may have been the first to win a state championship in football, but it’s been a legacy of guys and young ladies that have come through these hallways that have went on to do a lot of successful things.”

In fact, when he and his staff termed South Oak Cliff “The Mecca,” it was an ode to the school’s history.

Oak Cliff was founded in 1887 by Thomas L. Marsalis and John S. Armstrong, who bought hundreds of acres of land on the south bank of the Trinity River. Marsalis soon gained complete control and built a steam-powered railway and a waterworks system. Attempting to develop an elite residential area, he also created the present-day Marsalis Park, which holds the Dallas Zoo, and a first-class hotel.

When an economic depression hit in 1893, Oak Cliff’s attraction as a vacation resort dwindled. Marsalis, who’d personally financed most of the development, went bankrupt. As a result, the Dallas and Oak Cliff Real Estate Company subdivided the once-wealthy lots for the middle classes before the struggling town was annexed by Dallas in 1903.

But to this day, Oak Cliff is recognized as its own working-class community within southern Dallas.

South Oak Cliff High School was the first Dallas ISD school to integrate in 1967, and a school that operated for over a decade as an all-white institution became almost entirely Black within two years. Now in a present-day school district that is over 90 percent minority, there are South Oak Cliff graduates everywhere entrenched in leadership roles. Reginald Samples is a SOC grad. So is Adrian D. Bonner, the band director at Lancaster High, and Dallas Lincoln’s State Champion basketball coach Cedric Patterson. Almost everyone can claim at least one family member who attended South Oak Cliff, the home of integration in Dallas. The Mecca.

Those words are printed on Derrick Battie’s hat as he stands from the second-floor balcony and uses his 6-foot-10-inch frame to peer eye level at the pictures hanging in the Walk of Fame. He’s quick to point out that there’s space to add more murals, an expectation that this school isn’t done producing difference-makers yet.

“Now you walk in the legacy and history of all South Oak Cliff Golden Bears,” Battie says. “One day, they may put more pictures up there when it’s all said and done.”

One day they may add Battie.

Thirty years ago, Battie was competing in back-to-back state championship games on South Oak Cliff’s basketball team, winning his senior year in 1992 before playing at Temple University and then six years overseas. He was called back home to southern Dallas in the early 2000s to help his mother care for his terminally ill grandmother.

At first, he just helped out as a part-time assistant on the basketball team mentoring two 7-footers. That soon morphed into then-principal Donald Moten asking him to monitor the halls to stop fights in an overcrowded building. He ended up serving as Head of Campus Security for 16 years.

But when principal Willie Johnson was hired in 2017, he had a new role in mind for Battie. As a community liaison, Battie could better connect with the Oak Cliff neighborhood.

He spends his working days in The Dock, a large warehouse unit stationed in the back of the school. Yes, the extensive renovation from the 2015 bond program gave South Oak Cliff equal resources in their school facilities, but it also allowed them to build The Dock, and this is where Battie’s role with a student population floating on the poverty line comes into full focus.

“Ain’t nothing like South Oak Cliff. Now y’all know where we keep all the magic at.”

Battie manages two resource centers in the school building that were born in 2019 through a partnership with Frito Lay and the “Southern Dallas Thrives” initiative. They were meant to help the roughly 65 homeless students attending South Oak Cliff and their families, but they’ve morphed into centers where any student and any community member can come in a time of need. One center provides snacks and school supplies, and another has clothes for those who don’t have enough at home to stay within the dress code five days a week.

“What we’re going to do is try our best to make sure we can supply every wraparound service,” Battie said. “So when they got to campus, they would have no needs. There was no excuse not to be in class.”

Battie is all business when he ducks into a side room located in the back of the building. He and the volunteers here now need to create a conveyor belt-like workstation to unload a donation of backpacks, school supplies and shirts from Cynthia Marshall, the CEO of the Dallas Mavericks. Battie instructs his force to take one of the backpacks and put three pencils, a spiral notebook and a shirt in it so they’re ready to hand out to the students.

“Ain’t nothing like South Oak Cliff,” Battie says. “Now y’all know where we keep all the magic at.”

He quickly rattles off the names of the volunteers he’s conducting today. The president of the PTA is here, as is a Dallas Carter alum who helps at the school often. But he pauses on Torian Johnson, a YoungLife staff member. Johnson graduated from South Oak Cliff in 2016, before the renovated school. Before there was even a plan to renovate the school.

“He was here during the protest,” Battie says. “He understood that they had to do what they had to do in order for us to even be here.”

Part 2 of 3 will be released later this week.

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.