INGRAM, Texas - - Perry McAshan-McCall walks through her family’s Hill Country property that they’ve owned since 1944. Her grandmother, Edith McAshan, was a painter, and this plot of land had the peaceful, scenic views that inspired her art.

Now, Perry’s voice paints the scene of what happened just two weeks ago.

First up, Edith’s art studio.

“It was a studio with a northern light, and that’s evidently really good light,” Perry said. “And of course, as you see, the whole wall came out. It had two windows over here, and of course a wall. This is the most destroyed of all of our buildings.”

Across the yard was a cottage Perry’s parents built so they could live separately from mom and dad while her father recuperated from crash landing his Grumman Avengers airplane in World War II.

“Over the years, it’s grown. My mother added a bedroom loft, and she had a huge piece of furniture over here,” she said, pointing instead to ripped up floorboards. “It was really nice!”

Over 76 summers, this house became a part of her family, one of the last physical things she shared with her grandparents and parents who passed away. She and her husband, Michael, live in Houston, but they rented this place in order to pay the insurance, the yard man and the pool guy. To justify keeping it.

Then, in just 45 minutes on the morning of July 4, the Guadalupe River rose 26 feet and washed all that history away.

Perry’s home is in the Bumble Bee subdivision of Ingram, the hardest hit neighborhood in the second deadliest flood in Texas history, officially with 135 lives lost. The creek bed that runs behind the neighborhood, Bumble Bee Creek, hadn’t seen a drop of water in six years due to drought. But when the Guadalupe surged, it ran up against the rock bluffs that give the Hill Country its beauty, flowed into Bee Creek, and put their subdivision in the middle of a perfect, horrible storm. Every house was totaled.

“It’s just so sad to see it all gone,” Perry says.

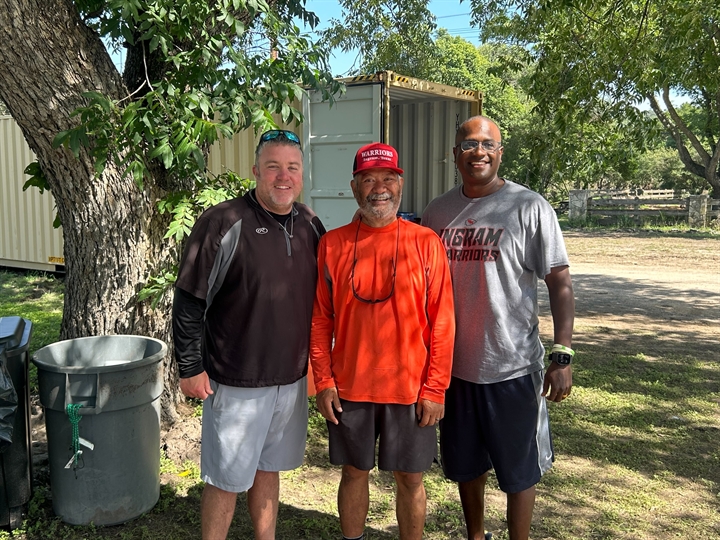

At this moment, the man beside her perks up. Tate DeMasco, the head football coach at Ingram Tom Moore High School, has been mostly silent as he’s followed along for the tour, listening intently and laughing along at Perry’s jokes. The woman is in remarkably good spirits. But at the first hint of how despondent this flood has left her, he throws a life raft.

“Did I hear you say it’s so sad?” DeMasco asks. “We’re over sad. We’re going to get this built back better.”

The question is how. Perry, like every member of Bumble Bee, doesn’t have flood insurance. The Guadalupe is 500 yards away, too far to think about paying for insurance in a neighborhood where there’s not much extra cash on hand. Before the fourth, Perry was a retired high school teacher from Houston Memorial. Now, her full-time job is restoring her family’s memories.

DeMasco knows how dire this situation is as he drives around in an Ingram ISD pickup truck loaded with hot meals for those in need. He admits how concerned he is for the small businesses and houses this flood wrecked. But the second that door opens to the world, the smile is back on his face and a quick joke is on the tip of his tongue. Because that’s what these people need even more than the meal he’s providing.

Before you leave, Perry needs you to sign the board. This slab of plywood is her most prized possession after the flood took the rest away. It’s covered in Black sharpie, hundreds of signatures from people who traveled from Helotes, Buda, Dripping Springs and San Antonio, all to visit the house and help clean debris. Her husband points to certain names and speaks in awe of how this person led the cleanup crews and how that person prayed with them.

Two weeks ago, Perry and Michael drove in fear from Houston to Ingram. Of course, they were scared of the damage they’d find. But the idea of rebuilding their lives alone brought panic.

Despite everything they lost, this board is proof of the community they’ve gained.

“We have lots to praise God about,” Perry said.

…

Since July 5, Tate DeMasco’s work day has started at 5:00 a.m. at CityWest Church. This is the command center for Ingram’s recovery effort. Mercy Chefs, in a partnership with the non-profit Blind Faith Foundation, cooks 4-5,000 hot meals per day in the parking lot. It’s up to DeMasco, his coaching staff, and anyone who’ll help to get those meals to the victims and first responders around town.

After checking in at the church, DeMasco runs Ingram Tom Moore High School’s summer strength and conditioning camp from 7-9:00 a.m. Then, he heads to his office to work on athletic director duties that are piling up. The school district’s superintendent retired a week before the flood, and the baseball coach quit days before. Oh, and fall camp starts in two weeks. But most of the time he’s on the phone coordinating which parts of town need what supplies to aid the recovery. Everything else is on the backburner.

By 10:00 a.m., DeMasco is back at the church with his entire staff, including the female coaches. They all huddle around a white board that gives assignments for how many meals go to each part of town. It’s like a pregame meeting, except every day is game day. The lunch and dinner runs take about four hours because every person they meet along the path wants to talk. Conversation provides a short break from the 12-hour days of hard labor, and a chance to cope. DeMasco normally doesn’t return home until after 10:00 p.m.

This tragedy has provided Ingram Tom Moore with an opportunity to show the community the core values like selflessness and servant leadership that they always talk about.

“If we’re going to expect our kids in adverse situations to perform and overcome, then we have to be out in the front leading,” DeMasco said. “We have to lead by example and pull them along with us so that they can see that this is what’s supposed to be done in a time of need.”

But it’s not only the high school kids working four-hour shifts loading up meals and cleaning yards who’ll learn from this experience. The actual coaches kids in elementary and middle school run around the church together every day and go on meal runs with their parents. DeMasco looks out at his 11-year-old son, Ty, roughhousing with his friends near the church stage. One day, his son will have to lead through tragedy, whether that be a flood, fire or a disease. DeMasco hopes he remembers the time when he was a boy and the Guadalupe surged, and what his community did next.

DeMasco leading his staff in the church provides a glimpse into how he’s revitalized the Ingram athletic program in his four years. This past academic year was the first time in school history every sport made the playoffs, including football’s first playoff berth since 2018. He and his staff trade off-color jabs and a few well-timed cuss words, because God has a sense of humor. But when he leads, they follow.

“He’s turned from a respected person to a hero,” said Danny Burch, a retired West Texas Special Investigation officer whose sons are in Ingram’s athletic program. “He wears the cape right now.”

That cape weighs heavy on his shoulders, but DeMasco will never admit it. This is not some heroic effort on his part. In his mind, these duties are in his job description even if they weren’t mentioned in the interview. And the toll this storm has taken on him pales in comparison to the one it took on the people he comes face-to-face with every day.

DeMasco and his coaches’ faces are sunburned from the nose down from days on end in the Texas sun with a hat and sunglasses. He’s barely slept since the flood, partially because he doesn’t have much time and partially because the worry keeps him awake. Family time with his wife and two kids is spent in the car handing out meals, where they fill him in on the youth practices he's missing. He and most of the staff have not taken a day off.

“These people that have lost their places and lost family members and are having to clean up, they don’t get days off,” assistant coach Joel Hinton said. “If they take a day off, they’re in the same exact situation with the disaster.”

That’s why DeMasco doesn’t have time for most media inquiries. Reporters from CNN and Fox News have texted him multiple times to no response. He doesn’t want his words bent toward politics, because those debates don’t rebuild houses. When shown an admiring parent’s email about him to Dave Campbell’s Texas Football, he half-jokes he’s going to get on them. He is not the story, and he’s only telling his side of it because it could bring help to the story that matters.

Ingram is a town that exists in the in-between. There is no delineating mark of a town center. It doesn’t have its own trash service or curbed streets. Because of this, its encroached upon by Kerrville, the larger town six miles east. It’s difficult to distinguish where Kerrville ends and Ingram begins, which is why this area largely goes unmentioned in national coverage. But that doesn’t make the devastation any less real.

The high school consists of kids from Ingram and the even smaller town of Hunt, which only has a kindergarten through 8th grade campus. Hunt is where Camp Mystic is located, the all-girls private Christian summer camp where 27 campers and counselors perished.

There is one two-lane road that runs from Ingram to Mystic along the Guadalupe, and the rest are dirt, which makes the logistics of transporting forklifts and firetrucks for recovery a nightmare. Along that road are piles of debris that reach 15-20 feet high. They can’t be removed until the state ceases the search for the 100 people still missing, because there could be bodies buried within.

“The Friday after the flood was the first time I had made it past Ingram and into Kerrville,” said Bridget Symm, DeMasco’s volunteer athletic administration assistant. “It was like, ‘Life is normal here.’ There were people going to the grocery store and at the car wash. And it was just so dystopian 12 miles the other direction. It was a war zone.”

The search itself has no end in sight, because every time rain comes, the human divers and cadaver dogs must clear the lakes in Ingram over again in case a body was dislodged from under a log or hung up on bushes. Once the weather forecast clears, the town will drain these lakes and begin digging through the ten feet of sediment that’s formed below the water’s surface. The best-case scenario is that the digging only uncovers cars and cows.

Most townsfolk admit Ingram’s physical restoration will take years. The emotional restoration will be even longer.

The surrounding towns have rushed in to speed up the process. DeMasco highlights coaches like Bandera’s Joel Fontenot-Amedee, Kerrville Tivy’s Curtis Neill and Edna’s Jamie Dixon who’ve been instrumental to the effort. Dripping Springs head coach Galen Zimmerman brought 55 of his athletes and seven coaches to help clean the Bumble Bee neighborhood. For those who’ve come to help, the hardest part isn’t lugging around heavy equipment. It’s getting back in the car after a hard day’s work and seeing how much more there is to do.

“We were there with all these guys. We worked for hours and got a lot done,” Zimmerman said. “And then you’re driving out and it still looks the same.”

But the progress is found when you step out of the car and see the new bonds that have formed.

Miles Murayama is Ingram Tom Moore’s High School’s biggest fan. Every day when DeMasco honks his horn at the bottom of his street in the Bumble Bee neighborhood, Murayama sprints out of his house in his Warriors hat. He begs DeMasco to let him become a bus driver for the team. Murayama is recently retired from his job as a UPS driver, but he still has the CDL bus license. His wife, Martha, jokes that it stands for “Can’t Do Labor.” When it’s time to move heavy boxes, Miles sneaks down the road, leaving his phone so Martha has to shout down the street.

Miles’ talks with DeMasco have turned into his favorite part of the day. He’s a firm believer in born leaders, and he sees those traits in DeMasco.

“I’ve been in the army for 33 years. I see his character, and his drive,” Murayama said. “He’s the type of person that knows how to motivate somebody.”

Miles and DeMasco interact like old friends, but they first met each less than two weeks ago. He lives five minutes from Ingram Tom Moore’s stadium, and DeMasco would’ve never known who he was if not for the flood. This fall, Murayama will be in the stands every Friday night.

“It’s kind of sad something like this had to happen for us to get closer,” Murayama said.

While this flood broke Ingram into a million pieces, it will heal stronger with a newfound sense of community.

“The people there are lifting each other and giving each other hope,” Fontenot-Amedee said. “That hope is like a miracle when you see it.”

Volunteers who’ve walked through Ingram say it’s difficult to describe the emotions the devastated land brings. There are victims who’ve lost every earthly possession on each street, yet there are far more smiles and laughs than tears. One man has only his back porch left because his house is completely gutted, and he offered it up to assistant coaches if they needed to take a breather. Everyone is focused on how lucky they are to have what they still do.

“Your heart breaks on one end, and then it’s renewed on the other side,” Zimmerman said.

Before she was a volunteer assistant with the Ingram athletic program, Bridget Symm owned a restaurant and vineyard on 13 acres of land. The barn was a catering and storage area, but the most valuable cargo was a box of books inside. Bridget had received a Bible on her wedding day with her name and all of her family’s names engraved in it. That book was one of the first things she thought of when barn flooded.

A couple of days later while Symm was working at the fire station, a friend who’d been cleaning out on her property plopped a book down in front of her. She’d found the family Bible in the middle of a field, completely dry and without dirt.

There is no sugar coating that Ingram is a demolished town. But people who look among the wreckage long enough find signs of God. A month before the flood, Perry McAshan-McCall couldn’t renew the contract for a family of five with a small baby renting her cabin in Bumble Bee. She now considers the overused septic tank that caused it a miracle.

“There’s been so many God things in all of this,” Symm said. “I know there were many bad things. But God most definitely touched so much of this.”

Below is a link to the McCall-McAshan family's Go Fund Me to restore their property.

___

A before-and-after look of Perry's house (before photos courtesy of bumblebeelodge.com)

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.