Late in the Texas summer, like a cold front that comes to relieve the oppressive heat, hope arrives for weary Texans when Dave Campbell’s Texas Football arrives in stores and mailboxes from Beaumont to El Paso.

The magazine, published since 1960, inspires such devotion that diehards go from store to store to find their copy. They give them as gifts, mail them to Texas expats, or just take it with them to devour every word covering more than 1,500 high schools and 47 colleges, along with recruiting and pro football.

Over those past 65 years, Campbell became Texas’ version of John Madden, now known more for video games than his hall of fame NFL coaching career, or Michael Jordan, whose shoes will carry his name further than his legendary NBA career did. People buy Madden. They buy Jordans. They grab a Dave Campbell’s.

Campbell, who was born in 1925 outside Waco, died in December 2021 -- on a Friday night, naturally -- at 96. But in 2025, when he would’ve turned 100, his name resonates as loudly as ever.

“I think of him as the George Washington of Texas sportswriters,” said Kevin Sherrington, who’s spent four decades at The Dallas Morning News. “He set a standard and everyone respected it. For it to transcend generations really means something. Blackie [Sherrod] is the king of Texas sports writers and always will be from people who understand the business. But from a standpoint of influencing sports in Texas, Dave had a far greater and longer reach than Blackie did.”

From his home base of Waco, Campbell did it all without compromise. He loved his hometown, loved his Baylor Bears and began his journalism career as a copy boy at the Waco Tribune-Herald two days after his high school graduation before he began attending Baylor.

He dreamt of being a chemist, but focus was a problem. In a lab, he couldn’t take his eyes off the tennis courts outside. He decided maybe he’d just write about sports instead.

“And thank heavens for that because he would've been a horrible chemist,” joked his daughter, Julie Carlson. “Tennis was his first love by far.”

In 1943, Campbell was drafted and dispatched to World War II, where he earned a Bronze Star for combat duty in France and Germany in the 14th Armored Division of the 7th Army. He returned to Waco, Baylor and the Tribune-Herald in 1946, and never left.

It was there he met Reba Lou Weaver, a young reporter who had just returned from the scene of a horrific fatal car collision, badly shaken, when Campbell noticed she was trembling and having trouble typing. “Just tell me what happened, and I’ll try to help you,” he told her. Together, they got through the story. Then they got married a year later. Their partnership, which gave them two daughters, Becky and Julie, lasted more than 70 years, until her death in 2020 at 95.

“He had that humanity for a coworker at a time when there were relatively few women working in newspapers,” said David Barron, who retired from the Houston Chronicle in 2021 after spending nearly 50 years in Texas journalism. “I just think that that indicates his kindness. He was not just the typical scores and stats sports guy.”

Campbell graduated from Baylor in 1950 and became the sports editor of the Waco newspaper three years later. From his vantage point, he felt like national publications were sloppy covering his beloved Southwest Conference, an afterthought to the New York magazines. There were typos, factual errors, and even worse, one didn’t even include Baylor in its conference preview.

In 1959, when visiting the in-laws in Navasota, Reba became frustrated when Dave spent hours every day in a hammock in the front yard, but didn’t say anything. On the drive back to Waco, Dave told her he had an epiphany.

“I figured this all out. I'm going to start this magazine,” he told Reba on the way back to Waco, their daughter, Becky Roche said. “It's going to be called Texas Football.”

A week in a Navasota hammock changed sports journalism.

Campbell’s creation somehow made Texas’ fascination with football grow, all while shrinking the vastness of the state in the pre-internet days where tales of Panhandle legends were mysteries to East Texans.

“The magazine first came out when I was in high school, and a kid from Orange could read about the Ding Dong Daddies from Dumas,” said legendary Texas A&M coach R.C. Slocum, who recently officially retired after 53 years in maroon. “You'd hear about Borger who was really good back then, you'd read about Wichita Falls and some of those places you really didn't know. You knew it was somewhere out that way. But all of a sudden Dave Campbell's magazine brought all of that into reality.”

Reba’s kitchen table became the publishing office. Campbell and his Tribune-Herald sports staff of Hollis Biddle, Al Ward and Jim Montgomery, wrote, edited and designed the entire first edition in 1960, featuring Texas’ Jack Collins on the cover. It was an instant hit, selling out across the state, but Campbell decided to print another run, and wholesalers opted against restocking. He lost $5,000 -- the equivalent of about $55,000 today.

“He ended up dumping a lot of magazines in the Waco city dump, which is why the ones that survived are worth so much money,” said Barron, who later became the magazine’s managing editor from 1990 to 2004.

But Campbell’s spirit and his connections kept the dream afloat. Within a few years, the magazine became profitable and began to grow. So, too, did Campbell’s influence and his network.

Sherrington said there was a changing of the guard in sports journalism in that era. Fort Worth’s Dan Jenkins had been scooped up by Sports Illustrated to help cover the same things Campbell had prioritized. The old guard wasn’t much interested in the new generation of sportswriters. Campbell, Sherrington said, was always on the lookout for new talent, and was uniquely encouraging. Sherrington recalled a moment in the early 1980s in the Baylor press box where Campbell, who he admired but had never met, came to tell him how much he loved his work and that he’d nominated him for Texas Sportswriter of the Year.

“You could have knocked me over with a feather,” Sherrington said. “I just was so blown away that anybody would think of nominating me for that, much less Dave Campbell. Throughout my career, Dave always would call to tell me how much he enjoyed something I had written and it meant the world to me that he would do that.”

His reputation paid dividends when it came time to produce a magazine that required a lot of work for not a little money.

“The reason we did it was because it was Texas football, the Bible of Texas football, and because it was by Dave Campbell,” Sherrington said. “All of us wanted to do whatever we could for Dave because of how much he meant to all of us.”

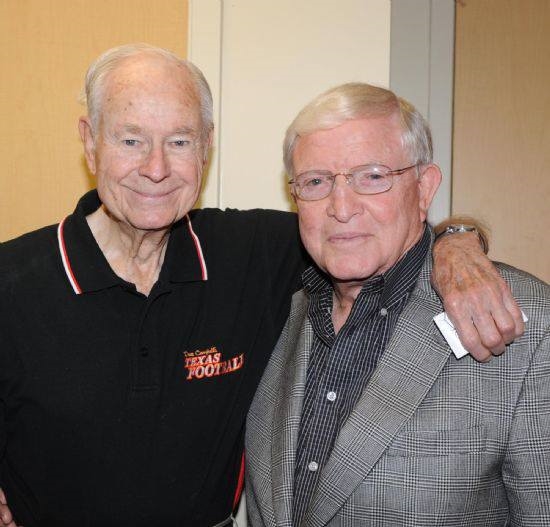

Campbell’s profile rose along with the success of the magazine. He was the president of the Football Writers Association of America during college football’s 100th anniversary. But he never got too big for Waco or for Baylor. Legendary Bears coach Grant Teaff, now 91, arrived in Waco at just 39 in 1972, making a big leap from Angelo State to one of the toughest jobs in football. His predecessor, Bill Beall, had gone 3-28 in three seasons.

“I was young and didn’t know boo from Sic ‘Em, so he kind of led me along the way,” Teaff said. “He was one of the top sportswriters in the United States of America, looked at far and wide. It was so great to have somebody with his knowledge and expertise that was a true friend. I've been around the block a time or two. I've been to New York City, I've been to Paris, I've been around the world, and I have never met a finer writer nor a finer man than Dave Campbell. I loved him.”

Campbell’s daughters said their lives -- and their house -- were filled with a quest for knowledge, for vacations, for reading books. Dave loved thrillers, mysteries, and World War II history, “probably to make sense of his time in the war,” said his daughter, Julie Carlson. He loved commiserating with authors, including once taking John Grisham to a Baylor baseball practice.

When James Michener wrote “Texas,” his 1,000-page novel that berthed the largest initial print run in Random House’s history, he came to Campbell for counsel on understanding the culture of the state.

“My special debt is to Dave Campbell of Waco, publisher of a spectacularly successful magazine about Texas football,” Michener wrote in the book’s acknowledgements. Campbell became friends with Willie Nelson, often being in his orbit around Darrell Royal and Frank Broyles.

“I was at a UT football game about two or three years ago and they're playing this clip of a young Willie Nelson, and I'm like, oh my gosh, that's my mom and dad in the background,” Roche said.

But as Campbell’s profile rose, he stayed the same.

“He was a real gentleman,” Slocum said. “When I was coaching, he would come down to visit every year before he'd do his magazine. He was a prince of a guy, loved football and he knew his stuff, but he put in the work to do it.”

Campbell continued serving as the Tribune-Herald’s sports editor for 40 years, until retiring in 1993. He sold the magazine to Host Communications in 1985, but remained as editor until 2021. There have been two more ownership changes, but no one will ever dare remove Campbell’s name from the title. Slocum said Campbell was a celebrity to coaches around the country who would look for any info to mine the state for talent before the advent of recruiting services.

“He is still a legend in sports, because other schools out of state would get those magazines,” Slocum said. “It was a great recruiting tool to see who the top players were in Texas.”

And he never stopped working, either, and Reba was always there.

“She should have been the MVP because she would go with them to all these sporting events and she was the one in the stands,” Roche said.

It wasn’t easy, because Campbell’s pregame and postgame work made for long days. Roche said her fondest sports memory was in her father’s later years, when Texas beat USC in the Rose Bowl to win the national championship after the 2005 season when her son Campbell was a sophomore at Texas.

“As we always did, we got to the stadium really, really early,” Roche said. “Five to six hours early, maybe more than that.”

They rode a shuttle from the hotel to the stadium, walked Dave to the media entrance, then went and tailgated. They watched one of the greatest games in college football history -- Dave said it was one of the two greatest games he’d ever seen along with the 1969 Texas-Arkansas game -- and then waited. And waited. And waited.

“We go back to the media entrance to wait for my dad to come out. We see Reggie Bush and Matt Leinart come out. This went on for hours. Finally my dad comes out and it's late, the stands are deserted, the parking lots are deserted, but he's just had the best time. The shuttles quit running. We don't have a ride, and it's before Uber. We're just walking along this thoroughfare and we're all just so excited, we don't even care.”

Finally, some Texas fans drive by and spot the contingent walking and ask them where they’re headed, before realizing the hotel is on their way. Everyone piles in, starts making small talk and introducing themselves.

“I’m Dave Campbell from Waco,’” he says.

The driver continues down the road in silence. A few minutes later, he quietly said, “I can’t believe we just picked up Dave Campbell.”

His people were everywhere. Even in prison. His family marveled upon discovering a cache of letters from Leon, an inmate in Huntsville, who was broken-hearted that someone in the joint had stolen his copy of Texas Football, saying you just couldn’t trust anybody anymore.

“Daddy sent him another copy and they struck up a correspondence for a while there,” Roche said. “He treated everyone with respect and kindness.”

Campbell loved carrying around a silver Sharpie and signing copies of the magazine for fans. Still, the family says they never quite understood how much he meant to Texans. It was fitting, they said, that a man who had lived and breathed Baylor sports and had been through so many lean years with the Bears, died when he did.

“He watched Baylor win the Big 12 championship and then after that he went into a very sharp decline and died a week later,” Carlson said. Still, she and her sister said they weren’t prepared for the outpouring of love following his death.

“He died about 7 o'clock on the Friday night on December 10th, and I called all my family to tell them,” Roche said. “Before I could barely get the last call off, someone said, ‘Oh, they just announced it at the [Austin] Westlake High School game, or they just announced it at this game.’ We just were so overwhelmed.”

Carlson said shortly after, she got a call from an unlisted number. Texas governor Greg Abbott was on the other end, asking the family to please consider a burial spot in the Texas State Cemetery, about a mile from the state capitol, reserved for “Texans who have made significant contributions to Texas history and culture in any number of fields, from artists and athletes to scientists and scholars.”

Carlson and Roche struggled with the decision. Here was someone whose life revolved around Waco, who never left. The man who helped get the Texas Sports Hall of Fame moved to Waco, which features a full-size replica of Campbell’s office, despite his modest objections.

Now, they would bury him in Austin? They had to make a quick decision, and it was agonizing.

They took a trip to see the cemetery, and were taken to the section where they could pick out a plot. And they looked around and realized how right it was.

“There was Coach Royal, cover of Texas Football,” Carlson said, before noticing the headstone of two other Longhorns legends. “There’s Cedric Benson, cover of Texas Football. There’s James Street, cover of Texas Football.”

It was a fitting resting place for a man who took the hard road to get there. His father died on Christmas when he was 7. He grew up with a single mother during the Great Depression, then suffered through the horrors of World War II. He came home and became a model husband, father and grandfather, all legacies he cherished more than having his name on a glossy cover.

“Here's this person who really had a very hard first 22 years of his life and could have easily been bitter or defeated, but instead it motivated him,” Carlson said. “I think he was just always so thankful and grateful for everything he had in every opportunity that it made him stronger. I think that's pretty remarkable.”

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.