Austin Eastside is the most unlikely playoff team in Texas high school football.

The Panthers endured 51 straight losses from 2017 through 2023, one of the state’s longest streaks. Head coach Luis Becerra was hired in the midst of that streak on July 9, 2018. At his first team meeting, four faces stared skeptically back at him. He had to hit the hallways to recruit his own students to the football team, miraculously convincing ten others to join. Austin Eastside scored 14 combined points in those first two seasons. The lack of numbers forced the coaches to field one football team across all four grade levels, creating a harrowing cycle of varsity teams composed almost exclusively of freshmen. Most would quit after one season.

The wins hadn’t come by the 2023 season, but Becerra and his staff had built enough interest in the program where they could have a freshman football team in addition to the varsity. From their first day on campus, Becerra told them their graduating class would be the group to change Austin Eastside football. That foundational group, now juniors, just earned the program’s first playoff appearance since 1991, when the school was called Austin Johnston.

“(As freshmen), I would say we were being role models to the varsity, even,” junior quarterback Aydan Aguilar said. “We were there at practice every day putting in that work and staying up in our classes. We knew what the next years held for us.”

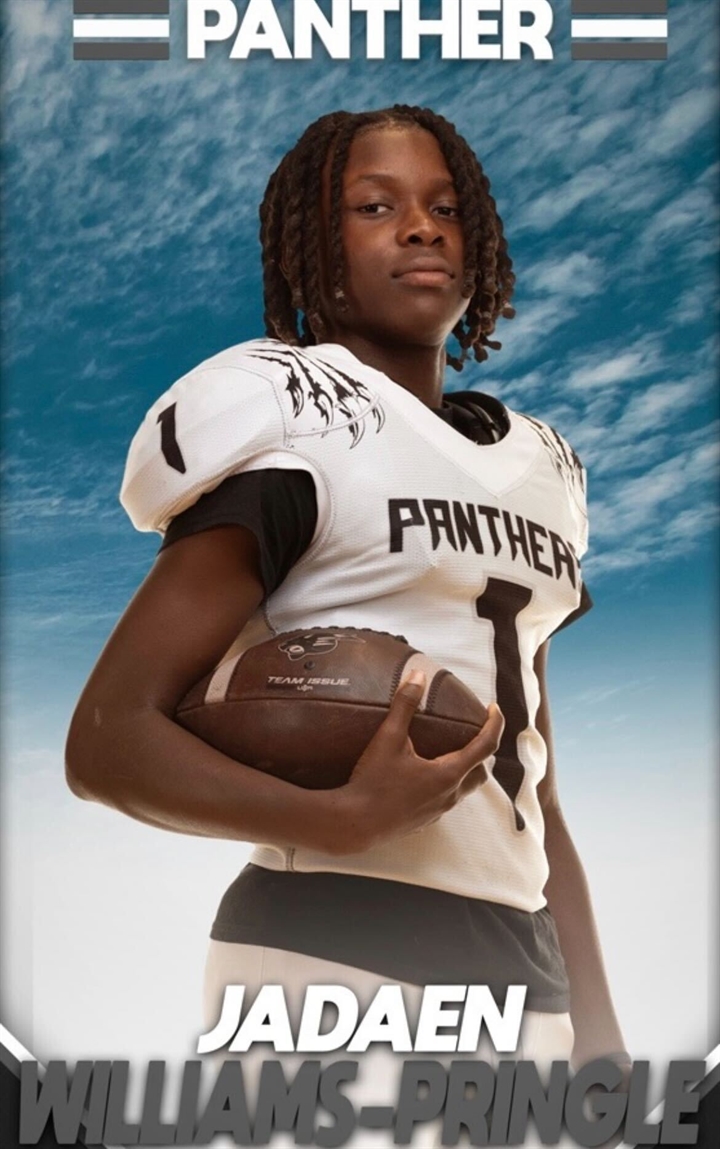

Much of that hope rested on the shoulders of quarterback Jadaen Williams-Pringle. Jadaen made football look fun. He seemingly always made the right decision, whether that be to sling it down the field or tuck it and scamper for a first down. But most importantly, Jadaen had swagger. It wasn’t the kind that boasted, ‘I’m better than you,’ but the kind that convinced his teammates, ‘You are better than you think you are.’

“He was a leader,” Aguilar said. “He knew how to bring people up and let them shine. When I first started playing quarterback, I didn’t know what I was doing. I just wanted to try because I saw him doing it, and it looked fun. He showed me the ropes and was a really good teacher and role model.”

Jadaen was raised by his grandmother, Joan Williams. She didn’t envision him becoming a football star. As a toddler, he couldn’t have cared less about the sport. Cars were his true love. He could hear an engine rev and tell you what kind of convertible it was and the horsepower it had. His entire wardrobe, including his backpack, had pictures of Lightning McQueen from the movie Cars.

When he was in elementary school, Joan’s friends Richard and Rocky Osborn reached out about playing in the i9 youth flag football league. Jadaen didn’t even want to play at first, begging Joan to stay home instead. But the first time he took off, he realized he could put down the Hot Wheels, pick up a football, and run like a racecar himself. Joan started filming the games, and Jadaen would study the tape on the ride home, explaining from the backseat how he could’ve cut a different direction to score a touchdown or could’ve taken a better angle to yank the flag.

“Football was Jadaen’s love,” Joan said. “I never thought something could come in place of his cars.”

And his new obsession was snapping Austin Eastside’s playoff drought. Joan would wake up at 2:00 a.m. to get a glass of water and see Jadaen’s bedroom lights on because he was watching HUDL. Once, after an especially close loss his freshman year, Jadaen broke down on the field because he thought he’d made a stupid move that cost a touchdown. He used to vent to Joan when he didn’t think his teammates were putting in enough effort at practice. Joan encouraged him to tell his teammates about his frustrations face-to-face rather than firing off texts in their group chat, which led to him being regarded as the team’s captain.

All these memories flooded back to Joan when she found out that Austin Eastside had made the playoffs last Friday. Jadaen Williams-Pringle passed away on November 8, 2024, from Stage IV Renal Cell Carcinoma. The Panthers’ playoff appearance completed Jadaen’s lifelong mission almost a year to the day after his death.

“When Coach Becerra texted me that they made the playoffs, I was like, ‘Oh, my God, Jadaen is rejoicing in heaven right now because that was his main goal,’” Joan said.

Jadaen is no longer under center, but if you look around Eastside’s program, you realize he’s here. Jadaen had the first locker in Eastside’s locker room, and his No. 1 jersey still hangs in it with a framed picture and his football cleats. The team wears helmet stickers that say ‘JWP #1.’ Every time the team breaks out of a huddle, they cry, ‘Uno on me, Uno on three. One, two, three, UNO!’ He deserves as much credit for this miracle season in death as he would’ve been lavished with in life.

Kids have asked Coach Becerra to wear the No. 1 jersey to honor Jadaen. But Jadaen left his heart on those sleeves. In Becerra’s mind, nobody could bear the weight of that uniform on their back.

“As long as I’m the head coach at Eastside, nobody will ever wear No. 1 again,” Becerra said.

Jadaen wasn’t just No.1, he was one-of-one. The team was so distraught when they found out Jadaen’s diagnosis last August that they had to cancel their scrimmage. The coaches used to visit Jadaen at the hospital and bring him an iPad so he could watch film from the team’s games. They’d ask how he was feeling, and he’d say he felt they should run this play against Austin Northeast because of a weakness he saw in their defense.

Jadaen approached cancer the same way he did his football career: dogged determination on a single goal. Before August 22, 2024, the goal was to get Austin Eastside into the playoffs. After that doctor’s appointment, his goal was to overcome cancer and get back on the field. He did not show any emotion when he was diagnosed. He was so steely, in fact, that Joan feared he was bottling his emotions up and allowed him to break one of her golden rules.

“Let me tell you something,” Joan said. “I don’t like cursing, but I give you permission. Let out your frustration. You can drop as many F-bombs as you want.”

“No MoMo (Joan’s grandmother name),” Jadaen said. “I’m gonna beat this.”

His diagnosis was effectively terminal, but his tumor actually shrank after two months of medication.

“You see,” Jadaen said, pointing at the PET scan. “You guys were crying about this, but I told you I’m going to beat it.”

During his hospital stay, a physical therapist would take him to a room to walk around and do some exercises every couple of days to break up the bed rest. The doctor had Jadaen toss a small medicine ball with his non-dominant hand. After the ball rolled a couple of feet from him, Jadaen decided to throw with his right hand. He prided himself on his quarterbacking ability, but by this time the tumors had spread to his kidney, liver and lungs, zapping him of his arm strength. The ball bounced at the same point as his left-handed throw. Unable to accept how weak he’d become, Jadaen asked for the ball again and again until he was sweating and out of breath. But the ball had reached the wall he was aiming for.

When the physical therapist came back for the next session a few days later, Jadaen was already perched up in bed.

“I was waiting for you,” Jadaen said. “What took you so long?”

That fight never left him, even when all his physical strength did. In his final days at home, Joan called the coaches to come see him one last time. When Coach Becerra walked in, Jadaen ripped the oxygen mask from under his nose.

The coaches would report back to the team with weekly updates on Jadaen. They told them his goal was to reach his 17th birthday on November 14th.

“Sadly, he didn’t make it to his next birthday,” Aguilar said. “But he did stay with us until the last game. We believe he was fighting to stay with us until the last game. It was really special to all of us.”

Now that Jadaen can no longer fight, the Panthers are working harder to keep his memory alive. During Pink Out Night this season, Joan served as an honorary captain, walking on the field with Jadaen’s jersey and a framed photograph of him.

“We miss him so much,” she remembers the boys telling her. “But we know he’s here with us. We can feel him all the time.”

Just as Jadaen is still in the hearts of this Austin Eastside football team, Joan does not go a day without thinking about her grandson. She couldn’t sleep in the months after his death because Jadaen would visit in her dreams. This past June, she heard rustling in his room. When she swung the door open, Jaedan was rummaging around.

“Jadaen, what are you doing?” Joan asked.

“What do you mean, Momo,” Jadaen responded. “It’s time for football practice.”

When Joan woke up, the clock read 4:30 a.m. That was the time every morning Jadaen got up for practice.

But Joan has stopped feeling haunted by his memory, and instead welcomes the reminders of him whenever they appear. Sometimes, she even talks to him, because she knows he can still hear her. After she read Becerra’s text that Austin Eastside made the playoffs, she looked up toward her grandson, just as she had looked up to him for his courage through cancer.

“Jadaen, I know you’re happy,” Joan said. “Look at what your boys are doing.”

This article is available to our Digital Subscribers.

Click "Subscribe Now" to see a list of subscription offers.

Already a Subscriber? Sign In to access this content.